It's strange to not have a therapist - therapy the Argentine way

A church in the neighbourhood dubbed ‘Villa Freud’ for its high amount of psychotherapist offices was only a 15 minute walk from my flat. All images are credited to the author of this article

My first night out in Buenos Aires on my year abroad would prove that it really is a city like no other. It might have been my first time drinking the Argentinian -famed Fernet, (a herbal alcohol mixed with coke), but it was also the first time I’ve ever met 5 psychotherapists standing in the same queue for the bathroom as me. This encounter was a real-life confirmation of the statistic I had heard before moving here- Argentina boasts of the highest number of therapists per citizen in the world . Despite being slightly bewildered by randomly meeting five psychotherapists at once, I began asking them about their work and why Argentina is so different in this respect, not only compared to Europe, but also to other South American countries. They suggested that this could be because Argentinians are generally more sociable and open, but this trait is certainly not only Argentinian, but is also regarded as South American. So, what is particular about Argentina’s culture which has led to such a normalisation of mental health care, and should we also adopt a similar mentality in the UK?

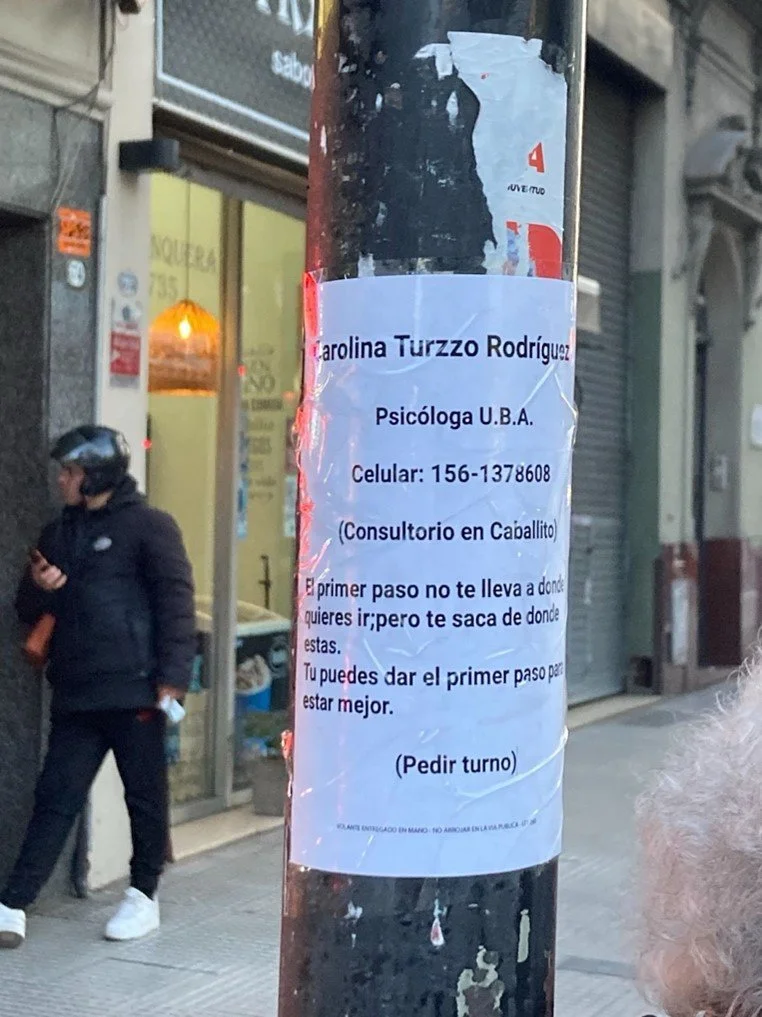

Flyer advertising therapy services near my faculty. In English: ‘The first step doesn’t take you where you want to be but it takes you away from where you are. You can take the first step to feel better.’

Could it be the stresses of economic security such as the inflation of 211%* that push Argentines to seek support through therapy, which, in turn, has normalised it socially? Could it be the fact that it is also one of the leading countries in Latin America for rates of plastic surgery, meaning that there is a cultural tendency to strive for mental as well as physical “perfection”, as some suggest? However, these therapists said that the most common problems people discuss are anxiety, depression, self esteem issues and, relationship problems, so it seems like Argentinians seek therapy for the same problems as most, regardless of nationality.

When I tried to enquire more, whether with close friends or almost strangers, almost everyone would talk very openly about mental health and therapy; for them, it seemed, having a therapist and openly talking about it was complete common ground. Many would also joke light-heartedly that “we Argentinians need it because of how crazy we all are”. Ironically, unlike the taboo in the West, it is in Argentina where it is recognised that you in fact do not need to be crazy in order to seek help.

Many friends would agree that it is almost strange if you don’t have or have never had a therapist. After explaining how differently therapy was viewed in England I was asked “so…in England when you feel bad what do you guys do to help yourselves?” and my struggle to answer the question was eye-opening. How do we help ourselves? I would say most people would just wait for the problems to pass or see it as an inevitable thing to endure because there isn’t much positive societal encouragement to seek therapy and taboos around it still exist. Admittedly, this has improved a lot in recent years with growing awareness surrounding mental health and the normalisation of therapy; some may even feel encouraged by the advice of NHS posters to talk to a friend, go for a run, try to eat more fruit or even go to a therapy session or two as a last resort. Withal, we still have a long way to go in terms of our attitude towards professional therapeutic help and it is nowhere near as integrated into everyday life as it is in Argentina.

It's also key to consider that the relatively recent rise of mental health awareness has mainly been distributed through social media, as we watch the rise of pop psychology terms such as love languages, attachment styles, gas-lighting and love-bombing flood Instagram and TikTok feeds. They have slowly seeped their way into public consciousness and this has clearly produced a growing demand for a culture that provides tools to grapple with our inner life. I do wonder, however, whether self-diagnosis from within internet echo chambers that reduce the complexities of dealing with the human psyche to “self-care days” is the best route to go down. It is again clear how far removed this is from the attitude in Argentina which encourages professional help.

In fact, their psychoanalytic culture is so integrated into society that while taking some psychology classes at the university teachers would open the class with saying how familiar and dear psychoanalysis was to everyone in the room as porteños (people from Buenos Aires), even to the extent that psychoanalytic language has trickled down into everyday colloquial speech. Many of these terms are derived from Freudian psychoanalysis, which still enjoys widespread respect and support, which comes about from the prospering Argentina of the early 20th century adopting European cultural advancements as such, like psychoanalysis. Consequent isolation due to dictatorships and economic downfall were one of the possible reasons why psychoanalysis remained such a strong discipline today while it lost popularity in the West, possibly also explaining its therapist culture today.

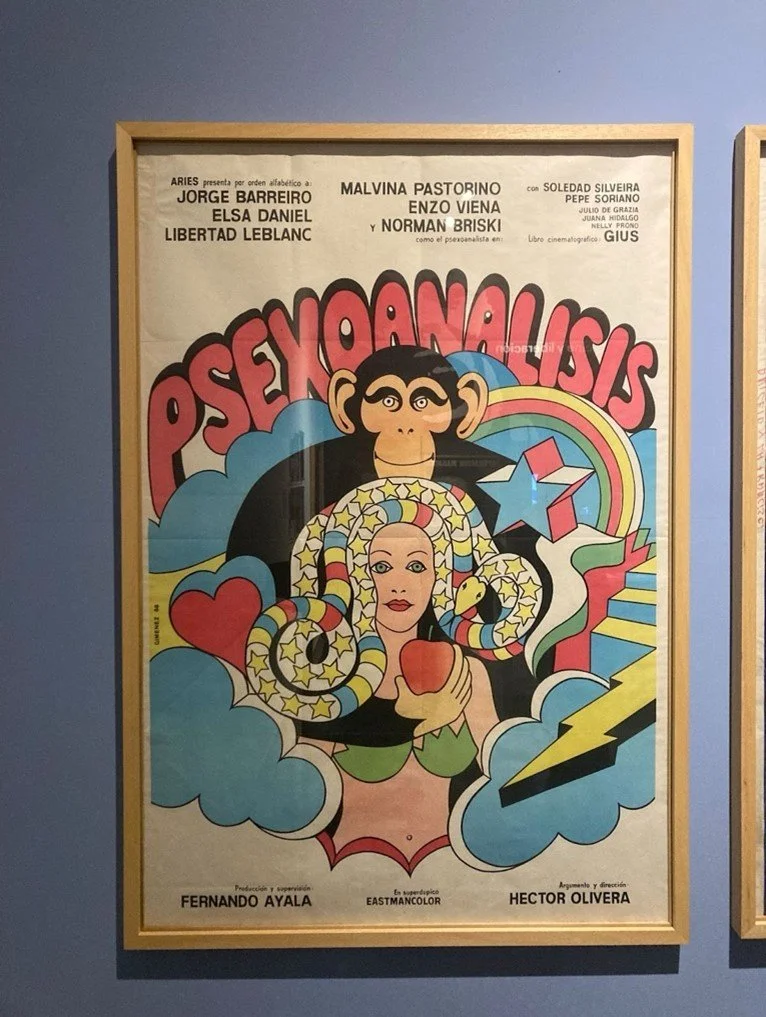

‘Psexoanalisis’ poster for the Argentinian 1968 comedy in the cinema museum, located in La Boca.

Is it all worth it then? Is the average Argentinian any happier than the average Brit who has never attended therapy? These are the questions I was desperate to find out. But after talking to an Argentinian friend, I realised how misguided this question is in the first place. She described a purpose of therapy that wouldn’t have crossed my mind before; to talk through positive experiences, to share happy moments with someone who is nonetheless an impartial and unbiased pair or ears. This would probably be seen as an unnecessary waste of time in the UK. This, more than anything, reveals that we may view therapy through the wrong lens. Such an alternative practice fundamentally goes against our usual concept that therapy should be an easy ‘fix’ for parts of you that are ‘wrong’ or ‘broken.’ Instead, it holistically acknowledges that positive experiences also play a big part of who we are, suggesting that therapy should be seen as a means of understanding yourself and not necessarily ‘fixing’ yourself.

Therefore, although some may identify problems with the Argentine system, such as the predominance of specifically Freudian psychoanalysis (though this is changing as more options like CBT therapy are becoming popular), we can undoubtedly learn from Argentina's open minded attitude towards mental health that removes, at least, the social taboo as a barrier from seeking help.

*inflation stat correct as of time article was written.