A Picture of Paper

By Tabitha Rubens

On the second floor of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, a shadowed doorway leads from bright white gallery space into darkness. A vast jungle landscape plucked from a fairy tale occupies the first room, and papier-mâché figures sit around a silver paper lake bordered by flickering amber lights. Here, we enter the carefully constructed world of Zhang Xu Zhan, the first Taiwanese artist to be named a Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year.

Zhang Xu Zhan was born in 1988, the year after the landmark lifting of martial law in Taiwan. For over 100 years, generations of Zhang’s family had managed the Hsin-Hsing Paper Sculpture Store, selling paper effigies in the Xinzhuang District of western New Taipei. Joss paper sculpture (the construction of human figures, buildings, and other objects from paper to be burnt for ritual purposes) has a rich history in Taiwan, having spread from China, where the craft originated during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). The creation of these elaborate structures was closely tied to local religion and the sculptures often featured in festivals and ceremonies. Traditionally, paper sculptures were burnt in honour of the dead; the burning of the sculptures was an outlet for grief, a means of connecting the mourners with the dead, and a way of transferring material items to the afterlife.

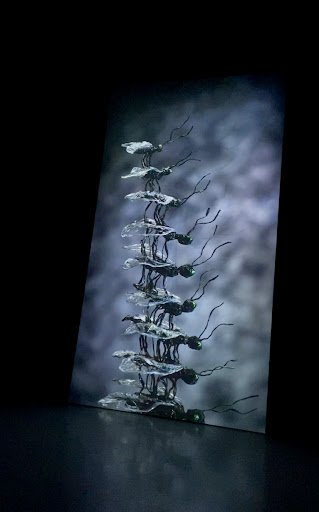

Pasted paper sculpture as an industry relies upon belief, however, and in recent years, this medium has lost traction. One by one paper sculpture stores have disappeared from the streets of Taiwan. Troubled by the decline of his family's industry, Zhang sought to revitalise the craft. His chosen strategy was to combine traditional techniques with an entirely modern phenomenon: animation. Zhang makes all his sculptures by hand, constructing comprehensive wire 'bones' which allow every detail of the body to be moved and animated. A 50cm sculpture takes him up to 10 days to complete. Zhang's experimental style has been repeatedly compared to Wes Anderson's surreal cinematography (primarily by Western commentators, though Zhang himself has also cited Anderson as an inspiration). The artist combines puppetry, digital imagery and sound design to create films that are in equal parts bizarre and enthralling.

The focal point of Zhang's Jungle Jungle exhibition is a 16-minute-long film titled Compound Eyes of Tropical. The gallery space in which this film plays has been transformed. From afar, the walls seem to be thick with moss and vine; step closer, however, and the textured surfaces are revealed to be newspapers dense with both Chinese and foreign language text, meticulously twisted into coils and ridges to resemble a forest floor. As you perch on a wooden bench, low whistles and hums rise and fall in an ominous soundscape. It is easy to slip into the illusion of sitting deep within a jungle as the film begins.

Compound Eyes of the Tropical depicts a mouse deer with a rust-coloured coat and silver legs dancing through a jungle as small bells fastened to its limbs jingle eerily. The creature crosses a river of crocodiles, evading the predators' snapping jaws by leaping nimbly across their backs. Having survived this perilous journey, the mouse deer throws its head back in delight, revealing a human figure beneath who clutches the delicate costume over his head. The film is interspersed with shots of similarly costumed figures beating skin drums, as well as hypnotic glimpses of scarlet lanterns spinning wildly between the trees. The climax comes when our adventurer - now fuelled by overconfidence - attempts to cross the river again, chasing after a fly with wafer-thin wings. As the figure leaps towards the bank, a crocodile tears off one of their tinfoil legs. The figure flails through the forest and shatters into shards of shimmering glass upon hitting the ground.

The plot is simple, but the stakes are high. The film serves as a commentary on the intersection of Taiwan's traditional culture with global influences. Survival is a central theme, and the audience is perpetually teased as dangers present themselves on screen. The beauty of paper sculpture is showcased throughout the screening, and the endurance of this ancient craft is closely tied to the fate of the little paper man struggling through a dark paper forest. Fundamentally, Jungle Jungle raises the question of how best to preserve traditions that are threatened in pluralised societies.

'Glocalisation' - the complementary rather than oppositionary relationship between globalisation and localisation - serves as a buzzword here. Zhang Xu Zhan’s influences are both local and international; he draws heavily from German folk songs to create a haunting musical score, for example, while the river-crossing draws from Indonesian folk legend. The movements of the characters are inspired by gestures from his observations of Taiwanese rituals, however. Zhang does well to strike a balance between maintaining the integrity of his family's art and engaging audiences familiar with more modern artistic forms. Paper sculpture lends itself well to the art of animation, and the stop-motion is beautifully executed. With exhibitions and features at the Museum of Decorative Arts of the Louvre, the International Short Film Festival in Berlin, the Shanghai Biennale, and the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, to name but a few, Zhang is elevating an endangered craft to an international stage.

Zhang Xu Zhan's exhibition reflects a trend among modern artists in Taiwan; many seek to conserve their unique identities and heritage while simultaneously embracing the challenges of modernity. In 2018, The Taipei Indigenous Contemporary Art Gallery displayed works by artist Etan Pavavalung, who aims to reinvent the Paiwan tradition of 've-ne-cik' (craft encompassing carving, embroidery, and writing) in order to start a dialogue about the place of indigenous art within contemporary society. Pavavalung turns to graphic art rather than animation, but, like Zhang, he complements traditional motifs and methods with modern art forms.

Exhibitions such as Pavalung's form part of the TICA's effort to reach a wider audience, and to propel indigenous Taiwanese art into the realm of popular and academic discourse. Zhang Xu Zhang's use of digital media and Etan Pavalung's incorporation of graphic styles illustrate that merging new and old can keep traditions alive. Zhang Xu Zhan's Jungle Jungle exhibition in particular challenges expectations for 'tradition' to remain static. Whether Zhang's modernisation qualifies as amelioration or necessary sacrifice is ultimately left to the viewer's discretion. Nevertheless, his work raises important questions about the meaning of 'preservation'.

Journalist Daria Lin notes that the appeal of the contemporary art scene is rapidly catching up with the food scene in Taiwan. A large part of this appeal is rooted in the innovation of artists such as Zhang Xu Zhan, for whom world-building is synonymous with artistic creation. Themes of identity and survival enhance Zhang’s artistry, resulting in an immensely impactful and original solo exhibition.

All images belong to the Tabitha Rubens, unless otherwise stated.