The Scandalous Non-Existence of Xue Mili

By Tabitha Rubens

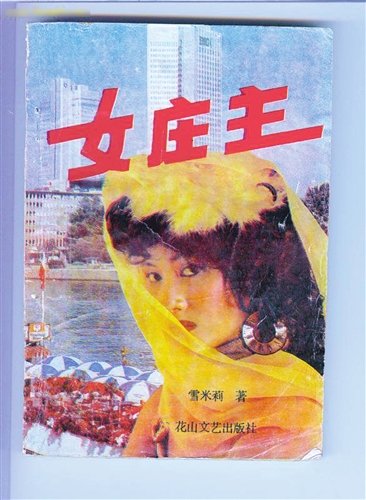

Cover of a Xue Mili novel (Image via Sina News)

In 1987, a new star entered the Chinese pulp fiction market. Cloaked in mystery, Xue Mili (雪米莉) kept a low profile; she made no public appearances, and accepted no interviews. All readers knew was that the author was a woman, and that she hailed from Hong Kong. Despite her elusiveness, Xue Mili's work was as popular as it was prolific. Her first novel soon had over one million copies in print, and within a year, Xue Mili had produced nine hit books. Each one told of beautiful women adventuring in metropolitan cities across the globe, and all used the character for 'female' (女) as a prefix in their titles. Female Chief, Femme Fatale, and Secret Policewoman offered flashy narratives - stories filled with gangsters, drugs, sex, and danger.

Formulaic as they were, these books flew off the shelves in the hundreds of thousands as Chinese pulp fiction readers were struck by 'Xue Mili Fever' (雪米莉热). The salacious stories and their seductive characters were soon plagiarised, countless rival writers grappling for a share of this profitable new market. Xue Mili had tapped into the rising demand for popular literature in late 1980s China.

Cover of a Xue Mili novel (Image via Baiku Baide)

Following Deng Xiaoping's drastic economic reforms in 1978, commercialisation was shifting national views of literature. No longer was the market controlled by government central planning; supply and demand gained real influence for the first time in decades. Interest in 'pure' literature and propaganda was usurped by a call for 'bestsellers'.

As the political, aesthetic and intrinsic value placed on literary work diminished, the financial potential of commercial fiction became the driving force behind Chinese literary markets. Xue Mili was one of the first to ride this wave. From 1987-89, she had gained considerable fame thanks to her popular series, and yet, the writer was nowhere to be seen. The only evidence of her existence was her remarkable ability to churn out a trashy but wildly successful read at the eye-watering rate of a book a month.

Then, on May 3 1989, Resonance Magazine published a damning exposé. The revelation read as follows:

“雪米莉”并非千娇百媚的香港女作家,而是两个川东汉子,准确地说是达县一群文学人。

“Xue Mili” is not, in fact, a bewitchingly charming woman writer from Hong Kong, but two Sichuanese men, or, more specifically, a group of literati from Da County.

The backlash within literary circles was immense, primarily because the two male writers heading this deception - or "literary prostitution", as some critics deemed it - had previously been respected writers of pure literature. Tian Yan Ning and Tan Li, both from Sichuan, had written celebrated short stories and novellas. Tan's acclaimed novel Blue Spotted Panther appeared in the esteemed journal October, while Tian won the National Short Story Award for his story The Mountain Road of the Cow Seller in 1989 - the very same year that the first Xue Mili book was published.

Yet, despite these accolades, throughout the 1980s, the pair had been finding it increasingly difficult to make a living. Both took their literary inspiration from rural life in Sichuan; while skillfully executed, their work held little appeal for urban readers, who monopolised the market at the time. Factionalism and corruption within literary circles presented further challenges for the young writers, and by the early 80s, Tian and Tan decided to shift their focus from the 'pure' to the 'popular'.

Xue Mili was the perfect guise. Capitalising on the boom in tabloids, magazines, and pulp fiction, the constructed identity offered a marketable persona to front books produced at breakneck speeds by Tian and Tan. Domestic literature at the time was dominated by writing from Hong Kong and Taiwan; the lovely Hong Kongnese Xue Mili was thus a marketing ploy, a glamorous and enigmatic figurehead for the series. Initially Xue Li, the character 'Mi', was added to the pseudonym to evoke the charming Hong Kong actress Mi Xue. Neither Tian nor Tan had ever set foot in Hong Kong, yet the allure of the region boosted sales and offered the perfect setting for many of the works in their series.

Covers of different Xue Mili books (Image via TW Great Daily)

The Xue Mili books proved so popular that Tian and Tan were soon unable to meet demand. In order to maximise profit, the pair expanded their operation, employing local literature students to help grow Xue Mili's fiction empire. Tian and Tan provided the overarching plot for each story and the students would then flesh out the narrative skeletons until they had a passable book. The group lifted plots from foreign films and based their cosmopolitan settings off descriptions from travel guides. Xue Mili was more than a mere pseudonym: she was an enterprise.

The reputational damage inflicted by the Xue Mili scandal was severe. However, Tian Yan Ning and Tan Li were simply responding to challenges faced by countless Chinese writers in the 1980s. So-called ‘serious’ writing held no market appeal. The uproar in the immediate wake of the exposé eventually subsided, and the Xue Mili brand continued to profit, bolstered by the increased attention brought by the scandal. Over ten years, 'Xue Mili' published more than 100 books and Tian and Tan made millions. In doing so, they were forced to sacrifice their ability to return to high literature.

The two-sided nature of the Xue Mili scandal reflects the changing face of Chinese literature as a whole in the late 1980s. During the 1990s, more writers would succumb to the financial temptations of the mass market, “writing down” in order to gain fame and fortune, or simply to make a living. Tian Yan Ning and Tan Li took this path before it was acceptable to straddle the divide between pure and popular. To proponents of pure literature, the creation of Xue Mili was traitorous - unforgivably so.

Hong Kong actress Mi Xue (Image via Jing Dian Lao Ge)