Josephine Baker becomes the first black woman to be honoured at Paris’ Panthéon

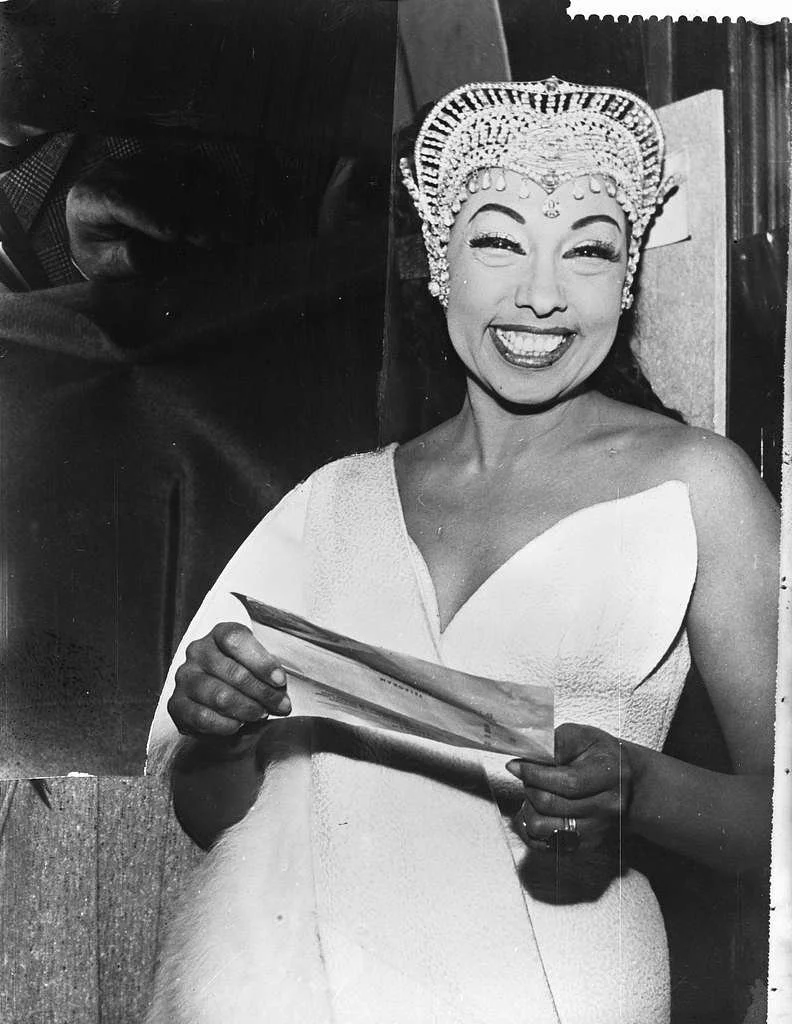

Josephine Baker c. 1925-1930. Image Credit: Allison Marchant on Flickr.

Josephine Baker (1906-1975) - a music-hall artist, member of the Second World War Resistance and leading civil rights activist - became, on Tuesday 30th November, the first black woman to be honoured at the Panthéon. Baker is only the sixth woman and the sixth person of colour to be enshrined in the Panthéon, the Parisian secular monument to “grands hommes” of the nation), joining the ranks of iconic figures such as Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Marie Curie and Aimé Césaire. Her panthéonisation was accompanied by full Republican pomp: a red carpet stretching up Rue Soufflot from the Jardin Luxembourg led the procession up to the mausoleum itself, where the white stone walls of the monument were lit up by images of Josephine in her music-hall prime.

From Saint-Louis to stardom

Josephine Baker began life quite differently. She was born in 1906 into an impoverished black family in Missouri. By the time she was fifteen she was living hand to mouth in the streets of Saint-Louis, had already been married twice and had witnessed the violent East St Louis race riots in which dozens of black inhabitants were killed and thousands left homeless. At age 19, having quarrelled with her mother and disgusted by the racism of segregation-era America, Baker emigrated to Paris.

Baker had already worked as a dancer in the States and quickly found her feet as a music-hall performer. In October 1925 Baker performed semi-nude wearing a garland of golden bananas as a skirt at the Théâtre de Champs-Elysées. Her dance ridiculed and subverted colonial-era exoticising fantasies about black women and turned Baker into an overnight star. She became a confidante of Cocteau and Sartre and a muse to Picasso: by the time she renounced her American citizenship to become French in 1937, she had become an icon of les années folles.

Josephine in Amsterdam in 1960. Image Credit: WikiCommons.

During the Second World War, Baker became a member of the French Resistance, using her musical tours as an excuse to transmit information for the Allies and mingling with Vichy politicians in order to gather intelligence. After the war, she became involved in the American Civil Rights Movement, even speaking before Martin Luther King in 1963 at the March on Washington in which he delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech.

In 1968, Baker was forced to move out of her castle in the Dordogne where she had been living with her twelve adopted children from across the world (what she called her “tribu arc en ciel”, her rainbow tribe) because of unpaid debts. She was given an apartment to live in by Princess Grace of Monaco, a close friend, and died after a coma in 1975, just days after a smash-hit show celebrating the bicentenary of her career.

Josephine’s relationship to France

This remarkable biography (soon to be serialised by ABC) was the main subject of Emmanuel Macron’s speech in the Panthéon, but the speech also touched on Baker’s broader significance as a symbol, not just an individual. Macron said that Baker was “infiniment juste, infiniment fraternelle, infiniment de France”, an advocate of “l’universalisme” who chose to live out her life in France because, in her eyes, it held “une promesse d’émancipation”. Baker - whose most famous song centres around the refrain, J’ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris - did indeed see in France an opportunity for freedom from the racism of segregation-era America.

Speaking to The Guardian in 1974, she said that she left America, which was “evil then” because she “just couldn’t stand [it]” and was traumatised by her childhood in East St Louis. At her speech at the March on Washington she said that when she arrived in France she felt it was like a “fairyland place”, and it was there that she was able to walk into “the palaces of kings and queens” whilst she “could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee”.

Josephine as a symbol ahead of the 2022 election campaign

Josephine Baker entered into the Panthéon on the 30th November therefore, not just as an artist, an activist and a resistance fighter, but also as an emblem of diversity, and evidence of historic openness in France: “elle incarne notre France plurielle, cette France éprise de liberté qui n'a pas peur du métissage et de l'ouverture à l'autre", affirmed Elisabeth Moreno, minister for Equality, Diversity and Equality of Opportunity.

Macron’s choice of Josephine Baker as a symbol of Frenchness may seem surprising to those aware of his immigration policies and his controversial efforts to counter “Islamic separatism”. His choice was a firm statement about the vision of France he will be touting ahead of the presidential elections in 2022. This vision of “une France conquérante et joyeuse”, according to Le Monde, situates itself in opposition to “la France défaitiste et recroquevillé représentée par Eric Zemmour”, the far-right journalist and polemicist who officially announced he would be running in the presidential elections on the same day as Baker’s panthéonisation. For Zemmour, Baker is not a symbol of a joyously diverse society, but it's opposite: the “assimilation à l’ancienne” he wants to restore. Critically, he is willing to celebrate her but only by making her an example of assimilative immigration: the implication is that if contemporary immigrants would assimilate like Josephine they too would be acceptable to him. The conflict in interpreting the legacy of Josephine Baker reflects the profound cleavage in French society on the question of immigration and immigrants’ relationship to their host country and its culture.

Ultimately, this conflict is not just about the politicisation of immigration models in contemporary France, but also about how the French relate to their history and how they perceive their country’s future. Followers of Zemmour are disappointed by the state of modern France - in response they call for a return to a bygone era of national pride and conservative Republicanism “à l’ancienne”, as Zemmour would put it. By choosing to honour Josephine Baker, who herself once said she had no interest in the past, and believed “in only the future”, Macron is trying to call on pride and hope as opposites of disgruntlement and nostalgia. Which interpretation is seen as more persuasive by the French electorate will, no doubt, become clear at the polls next April.