Reclaiming Afrikaans as a Language of Colour and Coexistence

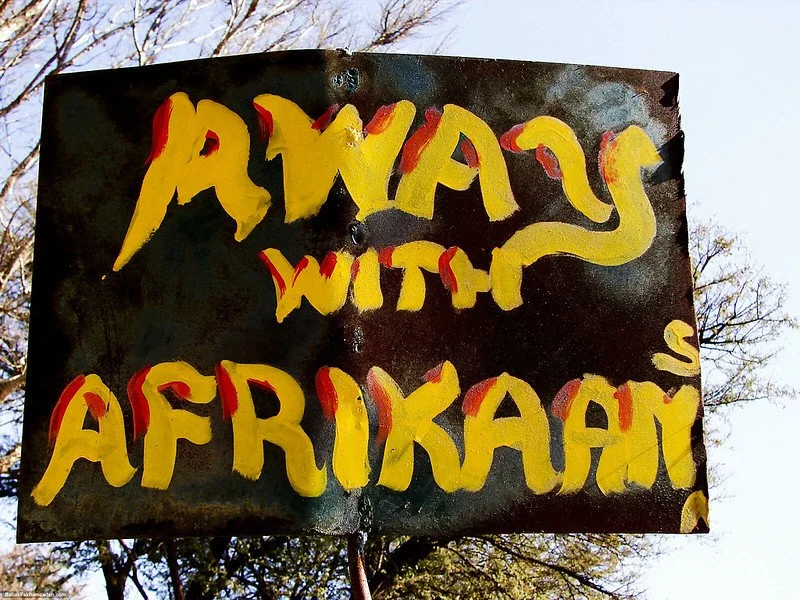

Away with Afrikaans (Babak Fakhamzadeh, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr)

Jake Altmann explores how one language can tell the story of South Africa.

Africa, usually the continent most consistently ignored by the Western news cycle, rocketed to the front page earlier this year as “white genocide” in South Africa became the latest target of President Trump’s arbitrary obsessions. Though Trump characteristically moved on from this talking point within days, South Africa is a place that the world could benefit from lingering on. South Africa has an important story to tell, and one of the most interesting manifestations of this story is in the languages of its population. South Africa has 12 official languages, all fascinating in their own right, but none tell the South African story quite like the country’s secondary national language: Afrikaans.

The Afrikaans tongue is simultaneously the language of the Apartheid regime, and of the non-white population it oppressed. It was the tongue of both colonizer and enslaved, now caught between calls for its removal from education as the language of Apartheid (as in the featured image) and pleas for its preservation as a language of heritage. In its vocabulary and grammar, though outwardly familiar to English eyes, clashes of cultures and continents can be discerned. Unravelling the story of Afrikaans exposes the heart of South Africa itself.

Afrikaans’ very name evokes the continent that is most distant and exotic to Western imaginations, but seeing the language in print will reveal something familiar. An anglophone tourist arriving in Cape Town will hardly be in need of a translation encountering a sign reading: “Welkom in Suid-Afrika.” For Afrikaans is a Germanic language, and its story begins at the same moment as the story of modern South Africa: in 1652, when the Dutch landed on the Cape of Africa. In contrast to most of Sub-Saharan Africa, the Cape’s almost Mediterranean climate drew European immigrants in large numbers. Not only Dutch settlers, but German mercenaries, Danish adventurers and French Protestants fleeing religious persecution. The blending of these groups created a novel people and culture – to their Dutch overlords, they were simply “Africans”: Afrikaners. And the unsophisticated form of Dutch that became their language? “African”: Afrikaans. Of course, South Africa had not been empty upon the Dutch arrival. The east was inhabited by dark-skinned Bantu peoples who had migrated from Central Africa over a thousand years previously, the Cape itself by the brown-skinned Khoisan, the region’s indigenous population going back over 50,000 years. To this diverse mix, the region’s Dutch and later British overlords also imported labourers from India and Indonesia. With the cast assembled, the stage was set for the next four centuries of South African history, showcasing both the clash and coexistence of cultures.

As the primary language of the Afrikaner population, it is tempting to straightforwardly assume Afrikaans to be little more than the language of white supremacy. The Apartheid Regime of South Africa’s late 20th century certainly imbued it with that perverse honour. Britain seized the Dutch Cape Colony in 1806, and the Afrikaners seethed and resisted against British domination for the next century, migrating beyond colonial borders to found their own republics, republics whose independence they fought to preserve to the bitter end in the Boer Wars of the 1880s and 90s. As South Africa was gradually granted autonomy and eventually independence from Britain in the early 20th century, Afrikaans was elevated over English as the primary national language: the language of a free South Africa. But the new South Africa that Afrikaans embodied was a white South Africa. Whilst the Afrikaners proudly trumpeted their freedom from imperial rule, the Black majority of South Africa’s population was quietly shepherded away from view into isolated “homelands” – territories that comprised 13% of the country’s land area, despite Black people comprising 68% of the population. But they were never too far away – indeed, they were readily harnessed as a de facto slave labour force to build the infrastructure, dig the mines and farm the soil of a nation that was, supposedly, a white man’s land. And the language that Black South Africans were taught – as Desmond Tutu observed: “just enough that they could understand instructions from their white bosses, but no more” – was Afrikaans.

Trilingual sign (JMK, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia)

To many in South Africa today, this is all Afrikaans is – the language of a bygone age of white supremacy. Since the coming of democracy in 1990, protests have seen Afrikaans demoted from the primary language of university instruction in 1994, to co-equal status with English in 2002, to secondary status in 2014. Today, South Africa’s governing coalition teeters as the African National Congress party considers legislation that would permit Afrikaans’ removal from schooling, to the fury of their coalition partners, the Democratic Alliance. These linguistic battles form one dimension of growing intercommunal tensions in modern South Africa. Though Nelson Mandela rejected calls for revenge in the aftermath of Apartheid’s fall, famously quipping: “resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies,” painfully immovable social inequalities have jaded a new generation of Black South Africans. Even today, three decades on from the fall of Apartheid, the white South African minority own 49% of urban land and 72% of agricultural land. A softer form of redistributive justice was seen in President Ramaphosa’s Land Expropriation Bill in January of this year, allowing the government to confiscate land from white farmers (sometimes without compensation) and redistribute it to members of other racial groups. In its sharper form, this ideology is heard in the populist refrain: “Shoot the farmer, kill the Boer!” In the past 18 years, almost 2,000 South Africans have been killed in racially-motivated farm attacks. The racial essentialism of three centuries of white rule has been turned on its head: this is a Black man’s land, where the Afrikaner and his language are not welcome. South Africa is fraying across more racial lines than just the Black-White: intercommunal violence between Black people and Indians flared up in the Durban Riots of 2021 where dozens were killed. After the fall of Apartheid, Mandela and Tutu wished for the new South Africa to become a “Rainbow Nation” that would find strength, not division, in its diversity – the country has made immense progress since then, but it is still pursuing this ideal.

But lift up the hood on the Afrikaans tongue, and the result may come as a surprise. The word for cannabis, dagga, derives from Khoisan dacha, while sembien (banana) is from Malay. Afrikaans is not just a suntanned variety of colonial Dutch, it reflects a long history of cultural exchange that has taken place beneath the stormy surface of South Africa’s history.

Even outside the Black “homelands,” white South Africa was never completely white. From the very beginning, relationships between white settlers, the indigenous Khoisan and imported South Asian slaves created a new people: the mixed-race “Cape Coloureds” – though problematic in America, that term is entirely normal in South Africa. Not white enough for full citizenship, nor Black enough for the homelands, the Coloureds came to form a racial middle-class of domestic servants and urban workers. It was primarily on their lips that Afrikaans formed its distinctive sound, and it is to them that the language primarily belongs today: 69% of its native speakers in South Africa today are Coloureds. Their dialect of the language, Afrikaaps, is its most widely-spoken form, and recent decades have seen it blossom as a language of music, film and literature.

Cape Coloured children (Henry M. Trotter, licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal, via Wikimedia)

In fact, in the 1700s, when British takeover lay in the future and had not yet ignited Afrikaner nationalism, what would become Afrikaans was dismissed by white elites as kombuistaal (kitchen-talk) for it was primarily the language of their Coloured and South Asian subordinates. Afrikaans’ creole origins are tellingly reflected in its grammar. Dutch irregularities, learned imperfectly by non-Europeans, were streamlined. Where Dutch (like English) irregularises the verb “to be” – ik ben, jij bent, hij is – Afrikaans simplifies to ik is, jy is, hy is, literally: “I is, you is, he is.” Viewed through this particular lens, Afrikaans transforms, chameleon-like, from a language of white rulers to that of colonial ruled, more akin to Jamaican Patois than American English.

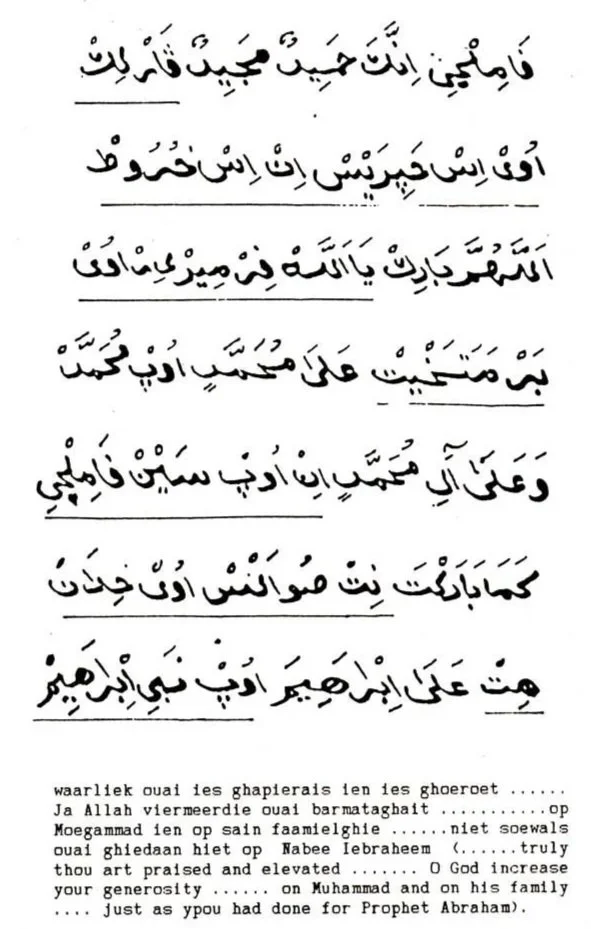

Due to the proximity in which Afrikaners (and especially their children) lived to their subjects, this “kitchen-talk” was gradually adopted into their speech. However, for many decades it was only the language of informal conversation, with European Dutch remaining the language of officialdom and writing until the late 19th century. This diglossia had a remarkable unexpected consequence: the first instances of written Afrikaans are not in the Latin script but make use of Arabic letters. While white Afrikaners were dutifully writing in a Dutch language they no longer spoke like medieval monks writing in long-dead Latin, it was the Cape Malays (a community of Indonesian descent) that first began to write in the colloquial creole of the Cape in the early 19th century. And, as Muslims, they wrote it in the script they knew best: Arabic. This lasted until the turn of the 20th century, a collision of worlds that only a place as extraordinary as South Africa could make possible.

Arabic Afrikaans, 1860 (زكريا, licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal, via Wikimedia)

Indeed, the discoveries of modern science bring unexpected surprises for white Afrikaners too. DNA evidence finds Afrikaners to have around 10% non-white heritage – mostly Khoisan and Indian. This is a relic of the first few generations of Dutch rule in the Cape, when the colour line was more porous. Freed slaves owned land, married into white families, and passed on their genes even if their origins were later forgotten or hidden. In 1947, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts proclaimed: “I am proud of the clean European society we have built here in South Africa.” How shocked would he have been to learn that neither he, nor any of his fellow Afrikaners, were “purely European,” but only a lighter shade of Coloured? But this genetic discovery has been welcomed by a modern generation of Afrikaners as a sign of their belonging in a multiracial South Africa. The author Cato Pedder, Smuts’ great-granddaughter, writes of receiving her own DNA test results with a mixture of pride and careful self-awareness: “There I am: colonialist, [but] South African.” Coloured and Afrikaner alike share the same mixed origins as their tongue.

Though South Africa’s leaders once proclaimed it a white man’s land, and its modern populists declare it a Black man’s land, beneath these nationalist fictions, something incredible is waiting to be known. Afrikaans is a language of contradictions. Its name means “African” yet it belongs to the family of European languages. It was derided by Afrikaners in the 18th and 19th centuries, before becoming a keystone of their identity in the 20th. And today it is denounced as something foreign, despite having the diverse history, culture and peoples of South Africa written into its linguistic DNA. Afrikaans demonstrates that South Africa’s history is not binary, but braided. Somewhere in the complexities of these stories is a path out of South Africa’s troubled past that refuses to disappear, a path that leads to the true fulfilment of Nelson Mandela’s vision.